Richard Nixon’s Venezuelan Lesson

In Latin America, Tuesday the 13th is usually considered a day of potential bad luck. The superstition is supposedly a combination of Roman God Mars, who gives his name to Martes (Tuesday) and is associated with war and destruction, and the number 13, usually associated with misfortune. As such, the most superstitious call for avoiding “risky business” on Tuesday the 13th.

By all accounts, Richard Nixon did not heed the advice. And so, on Tuesday, May 13, 1958, at 11 am, the then vice president in the Dwight Eisenhower administration landed in Maiquetía, Venezuela.

Nixon was arriving from Colombia, and our country was the last stop on his 18-day “goodwill tour” of Latin America.

Apart from the Cold War context, Venezuela had just witnessed the fall of the Marcos Pérez Jiménez dictatorship as a result of a popular and military uprising. Against this tense background, Washington wanted to know if it could count on the new government, but failed to account for a more important factor: the Venezuelan people.

The people did not forget that the US government had awarded Pérez Jiménez the Legion of Merit and had granted him political asylum after his fall from power. At the same time, leftist organizations like the Communist Party showcased a strong mobilization ability to go along with a fierce anti-imperialist discourse.

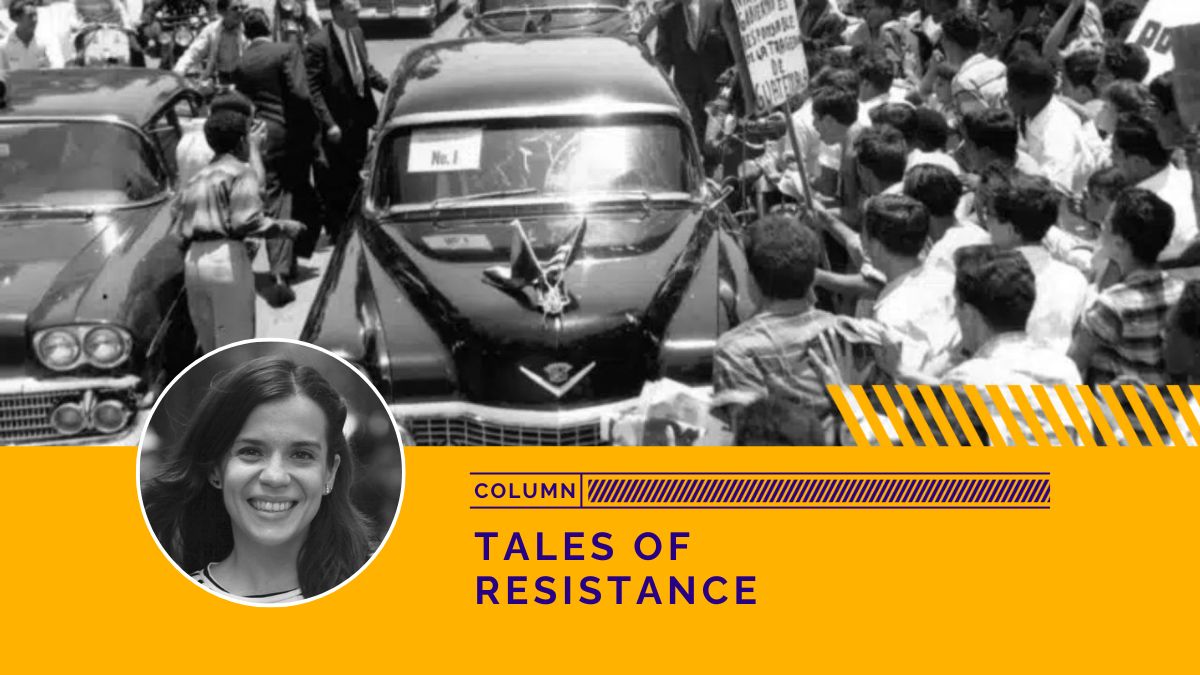

Nixon’s welcome was swift. Still in the airport, as the US anthem rang in the air, a crowd of angry Venezuelans began to shout slogans and insults at the foreign dignitary, who took his wife, Pat, by the hand and tried to defuse the situation by approaching the crowd. It was a bad idea, as both were spat on and Nixon almost had his suit torn off.

The unfriendly welcome saw the US Secret Service bundle the Nixons into a Cadillac and drive them to the National Pantheon for their next agenda item: a visit to the tomb of Venezuelan independence hero Simón Bolívar. But it seems like the Liberator’s spirit came alive through one of his most famous quotes: “the US appears destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.”

And so Bolívar’s soul took shape in another angry crowd awaiting the caravan in front of the historic monument, forcing the foreign delegation to turn around and head towards the US embassy.

Along the way, Nixon’s motorcade was again surrounded by protesters who banged pipes against the cars and threw stones, eggs, tomatoes and an assortment of other objects while unceremoniously telling the US vice president to go back home.

The embassy staff immediately reported the events to Eisenhower and he got in touch with the Navy’s Chief of Naval Operations, Arleigh Burke, ordering the immediate mobilization of the Fourth Pacific Fleet towards Venezuela. More than 1,000 paratroopers and marines were deployed in the Caribbean for an eventual rescue mission.

The US was on the brink of moving into Venezuela that day. But the Venezuelan people were not about to hide their feelings about Washington.

Fast forward 70 years and the US is at it again, with a major military deployment in the Caribbean Sea right on the edge of Venezuelan territory.

The Trump administration has confirmed at least four attacks against vessels in the Caribbean Sea, killing more than 20 people who were labeled as “narcoterrorists” by the White House despite no concrete evidence or intel being publicly disclosed. In truth, the entire “narcoterrorism” narrative against Venezuela resembles more a Hollywood script than a serious investigation.

Legal experts and some US representatives have strongly criticized the lethal operations, classing them as extrajudicial executions and violations of international law.

On the domestic front, the Maduro government has reacted to the new threats with military exercises and calls for volunteer enlistment in the Bolivarian Militia.

Today, just like in plenty of other moments in history, there are Venezuelans who want a political change. But according to a recent poll from Datanálisis, a pollster with anti-government leanings, 97 percent of Venezuelans reject the prospect of a US invasion of Venezuela. The majority wisely recalls the results of US interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya.

The main foreign invasion cheerleaders are abroad, in Miami above all, and the prospect of seeing tens of thousands of compatriots killed matters little to them.

At the same time, former White House adviser Juan González has claimed that the US Caribbean deployment is not only illegal but also an act of “political theater” by the Trump administration to strengthen its position before the Supreme Court while it awaits a ruling on its use of the Alien Enemies Act. Some analysts also back this thesis.

Theater or not, the danger is real. But it is clear that Trump’s domestic base is the “audience,” especially on the eve of midterm elections and with a resumé of foreign policy setbacks, from tariff wars to the war in Ukraine.

I’m reminded of how Nixon’s 1958 tour was a fiasco in terms of improving the US’ standing in Latin America, but he was greeted as a hero upon returning home. A crowd of 15,000, including Eisenhower, cabinet members and high-profile businessmen, welcomed Nixon and congratulated him for his handling of the tense situations.

Nevertheless, in his Six Crises memoir, Nixon placed the Caracas attack as one of the six most critical moments of his entire political career.

If the US went as far as launching an intervention in Venezuela and the region by extension, it would likely also prove to be one of Trump’s worst chapters. As Fidel Castro said in a 1980 speech, “There is something we don’t like: we don’t like to be threatened.” The struggle continues.

Jessica Dos Santos is a Venezuelan university professor, journalist and writer whose work has appeared in outlets such as RT, Épale CCS magazine and Investig’Action. She is the author of the book “Caracas en Alpargatas” (2018). She’s won the Aníbal Nazoa Journalism Prize in 2014 and received honorable mentions in the Simón Bolívar National Journalism prize in 2016 and 2018.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Venezuelanalysis editorial staff.

Translated by Venezuelanalysis.